Disclosure: This article may contain affiliate links. If you decide to make a purchase, I may make a small commission at no extra cost to you.

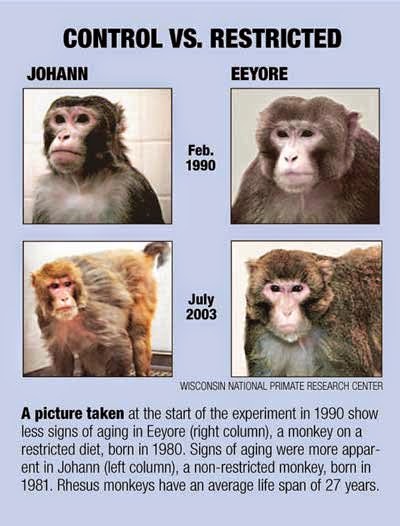

Since the 1980s, researchers have been conducting an experiment on rhesus monkeys by restricting their calories to see if a calorie restriction diet is beneficial for improving their health and longevity, as it does in other species such as yeast, worms, flies, spiders, rats, mice, dogs, cows, etc.

Rhesus monkeys live around 27 years on average and are thought to be the most similar physiologically to humans — so it’s believed the results would be translatable to humans. Pending the final results, I’ll go into what the current findings are and what they could mean for whether or not the work is likely to be translatable to people practicing calorie restriction.

Wisconsin calorie restriction study in rhesus monkeys

The study began in 1989 where they introduced 30 male rhesus monkeys into the study and then a further 30 females and 16 males in 1994. The animals were randomized and then put into either the control group or the calorie restricted group.

Reduction of calories was done in three stages, where food was cut by 10% at a time until they were restricted by 30%. The baseline was determined from monitoring the ad libitum food intake of each rhesus monkey.

The rhesus monkeys also received very good care, where any condition that developed during the study would be treated.

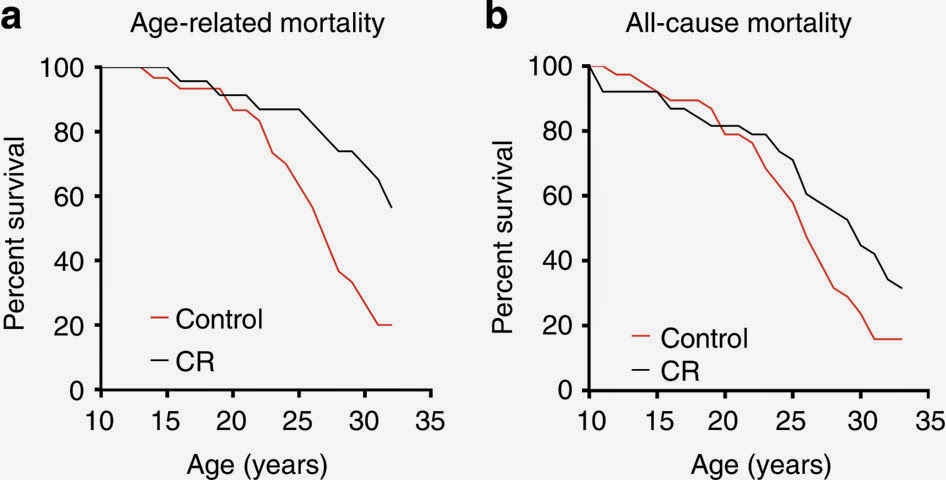

In 2009 we got a glimpse that calorie restriction in rhesus monkeys seemed to work and extended both healthspan and lifespan (1). Age-related mortality was slashed and control fed monkeys were 3-times more likely to die of age-associated diseases than the restricted monkeys. Although at this point, all-cause mortality between groups did not reach statistical significance.

The median survival for rhesus monkeys in captivity is about 26-27 years and a maximum lifespan of 40 years, with 10% reaching 35 years of age.

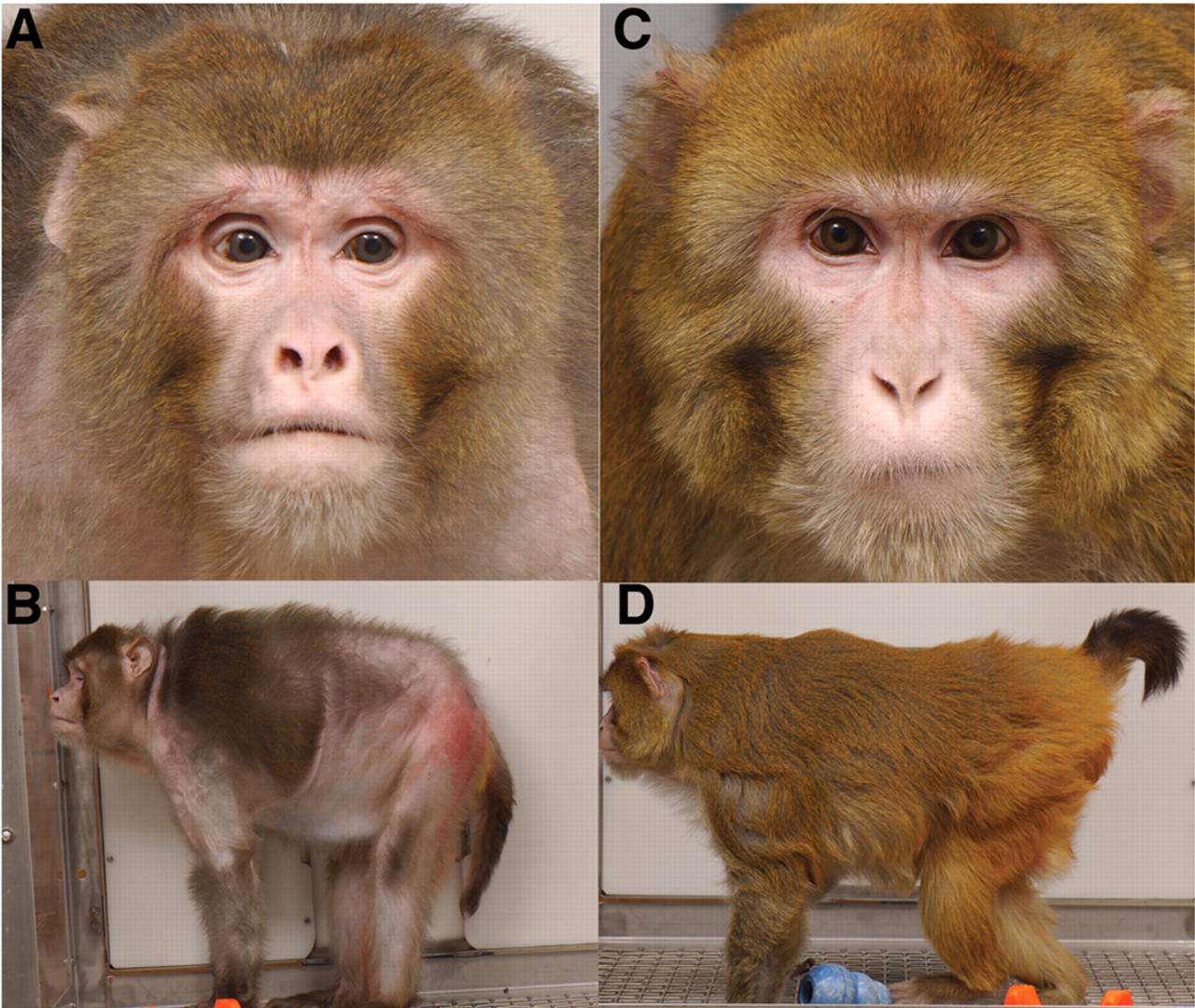

In this study, the calorie-restricted monkeys were far healthier and enjoyed complete protection from diabetes. They also had less heart disease, fewer rates of cancer, less muscle loss with age, less brain atrophy, among other benefits. It has been reported that calorie restriction monkeys also look a lot younger than their well-fed counterparts.

As you can see above in the survival curves, monkeys on a CR diet showed improved all-cause mortality and age-related mortality.

Age-related mortality includes deaths from cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, arthritis, etc.

All-cause mortality takes into account deaths from accidents, anesthesia, gastric bloat (accidentally caused by overcooked batches of food), and endometriosis (a non-fatal human disease).

Some of the deaths in the study could have been prevented and were not caused by intrinsic aging. So a separate analysis for just age-related mortality was created to look at the effect of CR on deaths caused by aging.

So far, 63% (24/38) of the control monkeys have died from age-related causes compared to only 26% (10/38) of the calorie restricted group. This indicates that simply reducing calories can have a dramatic impact on the incidence of diseases caused by aging.

For all-cause mortality, the control group had 1.8 times the risk of death from any cause compared to the CR group. Right now there are currently 12 CR monkeys and 6 Control fed monkeys still alive.

Date taken: May 2009

CR ‘anti-aging’ protocol

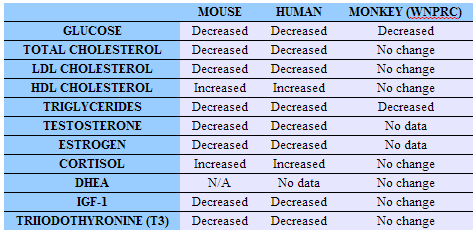

Although calorie restriction has improved average lifespan in the study at Wisconsin, the effects of the diet on the monkeys metabolic, lipid and hormonal profile has been inconsistent with the changes that are observed in mice, rats, and humans that are subjected to CR.

Reasons for this could be that the reduction in calorie intake was not sufficient to signal low energy availability to activate the pathways and responses that are involved in retarding aging in this species.

However, even with the inconsistent results, the monkeys still benefited from a reduction in calories and stayed lean throughout their life, as well as being much healthier and younger for longer.

A sweet disaster

To understand why there might have been a longevity advantage in the CR group relative to the control group, even though the CR monkeys did not display the CR-phenotype, we have to take a look at the diet used in the study.

The monkeys in the Wisconsin study were fed a semi-purified diet which comprised of 65% carbohydrates with 28.5% coming from sucrose, and the remainder from cornstarch. In the NIA study, the monkey chow comprised of 56% carbohydrates with only 3.9% coming from sucrose (3).

The high level of sucrose in the diet that the Wisconsin monkeys received could explain why there were more cases of diabetes in the control group compared to the NIA controls.

Although, interestingly, there were two cases of diabetes in the young-onset monkeys in the NIA study whereas the WNPRC study reported complete protection from diabetes in the CR monkeys.

Blood glucose levels were also lower in the Wisconsin monkeys, but they had higher levels of insulin in the control group. The CR diet brought it down to healthier levels. This is in contrast with the NIA monkeys, which had lower levels of insulin but slightly higher levels of glucose.

As mentioned earlier, before the monkeys were placed on the diet, they were monitored for a 3-6 month period to assess their caloric intake when they had free access to food, so that the researchers could establish an individual baseline from which to reduce the calories from.

Researchers found that the difference between the calorie restricted group and the control group dwindled to only 18% difference because the monkeys in the control group voluntarily reduced their calorie intake.

Monkeys normally do this with age, but this was fairly early in the study, so the researchers lowered the intake of the CR group further to establish a 30% difference once again.

However, there were some exceptions, where not all monkeys had their intakes reduced further because of the appearance of the animal, and it was deemed too risky to the animal’s health.

No further reductions in calorie intake in the CR group are being performed at this stage of the study, even if control animals still continue to decrease their intake in old age.

It was reported that 5 of the 38 monkeys of the Wisconsin control group developed full-blown diabetes, whereas only 5 out of 64 in the NIA control group (11% vs 8%). This indicates that the diet in the Wisconsin study may have been poorly selected. The NIA monkeys also weighed less at all ages than the WNPRC monkeys (2).

Compare this with humans: the prevalence of diabetes (diagnosed) in the UK is as high as 5.8% in England, with the national average at 4.6% in 2013 (4).

Longevity phenotype

A lot of research has gone into the biology of aging in recent years and it’s clear is that there is a specific phenotype that is common among long-lived individuals and families. Typically, they will have low levels of glucose and insulin.

Studies have shown a decreased functioning of the IGF-1 receptor and/or decreased levels of IGF-1 levels — which could be achieved by lowering protein intake to 10% of total calorie intake — leads to protection from diabetes, cancer and extends lifespan (5-8, 17).

Lower levels of thyroid hormones have also been found in people with exceptional longevity. Lower free T3, T4, and high-normal TSH can be exceptionally long-lived (9,10).

Higher HDL is protective, as well as low levels of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides (11).

in table 1 and 2, it shows the Wisconsin and NIA monkeys failed to display the changes that are typical with CR!

In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, men with lower insulin, lower body temperature, and high DHEA were found to be longer lived.

Humans who voluntarily do CR, display these changes with the exception of changes in T4 and TSH thyroid hormones, which is mixed in humans.

Overall, humans seem to be responding more favorably to calorie restriction and more closely matches the phenotype displayed mice and rats that have a dramatically extended lifespan.

Extra weight is not good for you

Several reports have come out in the last few years suggesting that being overweight decreases mortality, where they either show a J-curve or a U-curve for BMI,

They show that if you are thin, you have a greater risk of death, although being obese is even worse. Shockingly, the results suggested that being slightly overweight was actually good for you! (12).

Researchers came to this conclusion by looking at a large number of people and excluding all obvious causes of being thin such as smoking, alcohol abuse, and pre-existing diseases.

Unfortunately, these studies have many methodological flaws and the inability to control for leanness that is caused by a huge number of factors. Being thin does not equate to being on CR, and being on CR does not equate to eating healthily. Some condition might cause thinness even 10 years or more prior to death.

A healthy diet which is associated with leanness is good for you

Healthy individuals eating a diet that is rich in vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, and fish are likely to represent a very small fraction of lean individuals.

One study that was conducted by Cardiff University found that only 15 men out of 2,235 men ate more than 5 fruits and vegetables a day.

Less than 1% followed all 5 healthy behaviors. It’s clear that following a ‘healthy lifestyle’ is not common in the UK and US (13).

This study indicates that being thin in the general population is more likely to be a result of poor lifestyle choices or underlying diseases than to a healthy lifestyle.

In fact, just recently it was reported that eating 7 more fruits and vegetables a day is associated with a 42% reduction in mortality. And the more fruits and vegetables consumed, the lower a persons BMI! (14).

Back to the rhesus monkeys… Both Wisconsin and the NIA primate studies’ show that lowering body weight is very important to health and lifespan.

While there is a question to whether or not there is diminishing returns in the effect CR has on lifespan as body weight is, there should be no doubt that excess body weight is bad news when it comes to diseases of aging such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. And it’s important to remember that these are some of the biggest killers in western countries today.

These studies’ show that changing dietary habits can have a dramatic impact on your disease risk and that you have more control than you might think.

NIA RHESUS MONKEY CALORIE RESTRICTION STUDY

In the NIA study, they had two groups on the diet to establish what effects CR has on health in young animals and old animals.

The study conducted at NIA was more in-line with rodent experiments where the control group was restricted by 10% to avoid the effects of obesity, and the CR group are restricted by 30%.

Energy intakes were calculated from tables of energy intake requirements for the rhesus monkeys by age, weight, and gender.

Both groups received a relatively healthy diet that was also supplemented with 40% extra vitamins and minerals to ensure that the calorie restriction group met the recommended daily intake for all nutrients.

However, as the control group also received the same diet, this meant they were super-supplemented.

The diet given to the monkeys a more natural diet and contains many phytochemicals and other micronutrients that are beneficial to health. These could also act synergistically with CR to improve health.

During the course of the study, many measurements were made to see what effects CR had on the monkey’s health.

Young-onset CR

In the CR’d male monkeys, there was no effect on glucose levels compared with the controls, while in females, there was only a very slight reduction.

Triglycerides tended to increase with age across all groups. Interestingly, young-onset CR’d females experienced a significant increase in triglyceride levels compared to the control female group (15), which is bizarre, because, in humans, there are no differences by gender in the response to CR when it comes to the dramatic lowering of triglycerides.

The monkeys also failed to exhibit several other distinct changes that usually occur with CR.

There was no reduction in testosterone or estrogen as we see in rodents and humans. And no increase in the stress hormone cortisol (CR usually acts as a mild stressor.)

Serum triiodothyronine (T3) was reduced by 14% in the young and old CR’d female monkeys but there was very little effect in males.

In humans practicing vigorous CR, there is a major reduction in T, but this was not observed when overweight people who had lost weight to get within the healthy BMI range, like those in the CALERIE study (more on that later.)

Old-onset CR

In males, there was a significant decrease in cholesterol in the CR’d group. Glucose was also reduced significantly, while there was only a modest effect was seen in CR’d females.

Triglycerides were significantly reduced in CR males and modestly reduced in CR females (15).

Blood pressure was not affected in the monkeys, which is inconsistent with the data in humans, as we see a dramatic decrease in blood pressure from average values for their respective ages to levels that of a child: approx 100/60 (16).

These results are indicating once again that humans respond better than monkeys to CR.

CR has a dramatic effect on cancer if started young

So far none of the calorie-restricted monkeys have developed cancer (CR 0/40 vs 6/64 AL). Calorie restriction initiated early in life is powerful in protecting against cancer in rhesus monkeys and possibly humans.

This is one effect that is consistent with what we see in rodents. Unlike old-onset rhesus monkeys, the young-onset do see reductions in IGF-1 levels, which may partly explain this effect (although not entirely).

In humans practicing vigorous CR with protein restriction (10% of calories), both young and old see significant reductions in IGF-1. (17).

Longest lived rhesus monkeys on record

Although survival was the same for both groups in the old-onset group (35.4 years), this was significantly longer than previously reported median lifespan of just 27 years for a rhesus monkey in captivity (15).

Not only that, of the 20 male monkeys in the old-onset group, 4 monkeys in the calorie-restricted group have lived beyond 40 years compared with only 1 control monkey.

To put this in perspective, 40 years is considered the maximum lifespan for a rhesus monkey.

Researchers analyzed data on the lifespan of 3264 rhesus monkeys, and only two 40-year old monkeys have ever been documented!

According to researchers, one year for a monkey is roughly equivalent to 3 human years (1).

Does this mean that 35.4 years for a rhesus monkey would correspond to about 106 human years?

Rhesus monkeys in this study in both old-onset groups gained 8-years of extra life (equivalent to 24 human years.)

Waiting for the final results

As the study is still about 10 years away from being completed, I would expect that we could see a few more 40-year old monkeys in the young-onset group.

The NIA group had a fairly significant survival advantage over all groups in the Wisconsin study. With a 10% restricted healthy diet, the NIA cohort broke longevity records.

Is it possible that the 10% reduction in calories with a very healthy diet that was rich in vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, omega-3 fatty acids was additive in its effects with CR? And that the 10% CR group effectively got the same benefit as the 30% restricted group? Possibly.

As these monkeys have lived far beyond what is typical for a rhesus monkey, it’s clear that the quality of diet matters a lot and that being lean is very beneficial for health and longevity.

It’s worth noting that studies on rodents show that 10% CR can effectively extend lifespan as much as 30% for certain strains. However, in most, the lifespan gained is in proportion to the degree of restriction and the length of time the animal has been restricted.

Translation of ‘monkey years’ to ‘humans years’ might not be exact; it’s just a rough estimate.

What does this mean for CR working in humans?

At least 18 people practicing calorie restriction with optimal nutrition have been studied by Dr. Luigi Fontana at Washington University in St Louis.

In a study published in 2004, medical records were collected of the participant’s previous health data which included things such as body weight, blood pressure, glucose, cholesterol, etc, to see what effect years of calorie restriction has had on health.

Those doing calorie restriction were very lean: BMI of 19.6 ± 1.9 vs 25. ± 3.2 kg/m2. Average time on CR was 6 years ± 3 (range 3 to 15 years).

CR induces a younger gene expression profile in humans

Just recently participants from the CR society had their muscle biopsied and analyzed to look at gene expression profiles compared to that of 30-year-old controls and age-matched controls (58 years), and also they compared the molecular changes in rats on 40% CR.

They hypothesized that CR in humans would have induced a down-regulation of the Insulin/IGF-1/FOXO pathway which has been linked with longevity in animals and humans (20-22).

What they found was a very significant down-regulation of the Insulin/IGF-1/FOXO pathway at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. The key changes in skeletal muscle gene expression profile that are observed in long-lived rats are also observed in humans.

So not only are humans responding at a physiological level to CR as animals do, but the molecular adaptations seem to mirror that of mice and rats.

They also looked at SIRT 1 and AMPK: these two energy-sensing pathways were significantly up-regulated in people on CR.

FOXO3A and FOXO-4 were significantly up-regulated as well. These are known to modify many ‘longevity genes’ in animals and increase activities such as DNA repair, antioxidant defenses, immunity, protein turn over, and cell death genes (22).

Autophagy, which helps remove dysfunctional cell components, was also significantly up-regulated by CR.

Looking at (Figure 1b (23)), it looks as if people on CR had more similar gene expression profiles to the younger individuals in the study.

The ‘gene expression’ of people on CR is more like that of a 30-year-old than the age-matched 58-year old control group.

CR significantly improves cardiovascular health in humans

The average total cholesterol and LDL-C concentration for the CR group were in the lowest 10% for people in their age group (50 years).

Even more dramatic, the levels of triglycerides in the CR group were lower than 95% of Americans who are in their 20s. And their HDL (good cholesterol) was higher than 85-90% of people in middle age.

Fasting insulin was 65% lower than the western diet group and glucose was also significantly lower too. People on CR have also been found to have lower body temperature, lower thyroid hormone T3 as well, but people who exercise vigorously and maintained a similar BMI did not see these reductions (29, 31).

Participants of the study also had extremely low blood pressure, equivalent to that of a 10-year old. They had almost non-detectable or very low levels of inflammation measured by c-reactive protein.

IMT carotid artery thickness was measured and found to be 40% less in the CR group compared with the controls: 0.5 ± 0.1 mm in the CR and 0.8 ± 0.1 mm for controls.

None of those eating a CR diet had any evidence of atherosclerotic plaque.

To show the powerful effect that CR had on their health, the researchers were able to gather medical records from 12 of the individuals in the CR group and show that just like the western diet group, values for the CR group were average (50th percentile) before embarking on the diet.

Possibly even more impressive results showing that CR in humans might be slowing down the rate of aging of the heart.

They looked at the diastolic function of the heart and its ability to relax and fill the left ventricle and found that people on CR had hearts that were similar to those who were 15-years younger (17).

And those on the diet also had heart rate variability of a person 20 years younger (18).

Will calorie restriction work in humans?

Looking at the data we have thus far from mice, rats, rhesus monkeys, and humans, we are able to make comparisons to see the differences between each species in how they react at a molecular level and at the physiological level to CR.

It’s clear that people on a calorie restriction diet display a more CR-like state than either the NIA or Wisconsin rhesus monkey studies. This is promising for people that have been on a CR diet for many years in the hopes that it will extend their life.

People in the CALERIE study who were overweight and merely reduced their body weight to a ‘healthy’ weight from a BMI of 27 to 24 with 25% CR, never exhibited several CR signatures, nor did they have as significant reductions or changes in total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, inflammation, thyroid hormone levels, testosterone, estrogen, IGF-1 and cortisol.(26-28).

All of these are strongly influenced in people studied at WUSTL. These people are from the CR Society and practice moderate-severe CR. (16-19, 23).

Many of these signatures that were not observed in the CALERIE study were also either not observed in the CR primate studies, were very inconsistent, or modest in their change or effect (25-28).

This indicates that the level of CR in the primate studies, as well as the CALERIE human study, were insufficient to elicit the key changes that are responsible for the age-retarding effect of CR.

Aside from the level of CR being insufficient to elicit these changes, another possibility could be that the declining difference between energy intakes of the NIA rhesus monkeys (20% less than ad lib for males and only 12% for females) could be the reason why little differences were seen.

It was reported also that the calorie-restricted monkeys did not exhibit much sign of hunger during the study either. Yet another argument pointing to the fact that the CR group needed to be restricted further.

Before embarking on this very long study, it may have been wise to restrict monkeys to various degrees to see if there is a ‘cut-off point’ to where CR does not improve their health further.

If they display the CR-phenotype in a more consistent and powerful way, then establish this level of restriction for the CR group for a lifespan study, as long as the level of restriction was not inhumane and the animals did not display poor health from it.

References

1. Caloric Restriction Delays Disease Onset and Mortality in Rhesus Monkeys

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/325/5937/201.full

2. Ricki J. Colman, T. Mark Beasley, Joseph W. Kemnitz, Sterling C. Johnson, Richard Weindruch & Rozalyn M. Anderson. Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys

Nature Communications 5, Article number: 3557 doi:10.1038/ncomms4557

3. Kemnitz JW1, Weindruch R, Roecker EB, Crawford K, Kaufman PL, Ershler WB.

J Gerontol. 1993 Jan;48(1):B17-26.

Dietary restriction of adult male rhesus monkeys: design, methodology, and preliminary findings from the first year of study.

4. Diabetes prevelence in the UK (2013).

5. Solon-Biet SM, McMahon AC, Ballard JW, Ruohonen K, Wu LE5, Cogger VC, Warren A, Huang X, Pichaud N3, Melvin RG6, Gokarn R, Khalil M8, Turner N9, Cooney GJ, Sinclair DA, Raubenheimer D, Le Couteur DG, Simpson SJ.

The ratio of macronutrients, not caloric intake, dictates cardiometabolic health, aging, and longevity in ad libitum-fed mice. Cell Metab. 2014 Mar 4;19(3):418-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.009.

6. Levine ME, Suarez JA, Brandhorst S, Balasubramanian P, Cheng CW, Madia F, Fontana L, Mirisola MG, Guevara-Aguirre J, Wan J, Passarino G, Kennedy BK, Wei M, Cohen P, Crimmins EM, Longo VD

Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population. Cell Metab. 2014 Mar 4;19(3):407-17. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.006.

PMID: 24606898

7. Lorenzini A1, Salmon AB, Lerner C, Torres C, Ikeno Y, Motch S, McCarter R, Sell C.

Mice Producing Reduced Levels of Insulin-Like Growth Factor Type 1 Display an Increase in Maximum, but not Mean, Life Span. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014 Apr;69(4):410-9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt108. Epub 2013 Jul 20. PMID: 23873963

8. Milman S1, Atzmon G, Huffman DM, Wan J, Crandall JP, Cohen P, Barzilai N.

Low insulin-like growth factor-1 level predicts survival in humans with exceptional longevity.

Aging Cell. 2014 Mar 12. doi: 10.1111/acel.12213.

PMID: 24618355

9 . Adam Gesing1*, Andrzej Lewiński23 and Małgorzata Karbownik-Lewińska12

The thyroid gland and the process of aging; what is new?

10. Rozing MP1, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Slagboom PE, Beekman M, Frölich M,

de Craen AJ, Westendorp RG, van Heemst D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Nov;95(11):4979-84. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0875. Epub 2010 Aug 25 Familial longevity is associated with decreased thyroid function. PMID: 20739380

11. Rahilly-Tierney CR1, Spiro A 3rd, Vokonas P, Gaziano JM. Relation between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and survival to age 85 years in men (from the VA normative aging study). Am J Cardiol. 2011 Apr 15;107(8):1173-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.12.015. Epub 2011 Feb 4

PMID: 21296318

12. Flegal KM1, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI.

Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013 Jan 2;309(1):71-82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905.

PMID: 23280227

13. John Gallacher, Peter Elwood, Julieta Galante, Janet Pickering, Stephen Palmer, Antony Bayer, Yoav Ben-Shlomo, Marcus Longley, Healthy Lifestyles Reduce the Incidence of Chronic Diseases and Dementia: Evidence from the Caerphilly Cohort Study Published: December 09, 2013

14. Oyinlola Oyebode, Vanessa Gordon-Dseagu, Alice Walker, Jennifer S Mindell

Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality J Epidemiol Community Health doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203500

15. Julie A. Mattison, George S. Roth, T. Mark Beasley, Edward M. Tilmont, April M. Handy, Richard L. Herbert, Dan L. Longo, David B. Allison, Jennifer E. Young, Mark Bryant, Dennis Barnard, Walter F. Ward, Wenbo Qi, Donald K. Ingram & Rafael de Cabo. Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study. Nature 489, 318–321 (13 September 2012) doi:10.1038/nature11432

16.. Fontana L, Meyer TE, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Long-term calorie restriction is highly effective in reducing the risk for atherosclerosis in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Apr 27;101(17):6659-63. Epub 2004 Apr 19. PMID: 15096581

17. Fontana L, Weiss EP, Villareal DT, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Long-term effects of calorie or protein restriction on serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 concentration in humans. Aging Cell. 2008 Oct;7(5):681-7. PMID: 18843793

18. Meyer TE, Kovács SJ, Ehsani AA, Klein S, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Long-term caloric restriction ameliorates the decline in diastolic function in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Jan 17;47(2):398-402. PMID: 16412867.

19. Stein PK, Soare A, Meyer TE, Cangemi R, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Caloric restriction may reverse age-related autonomic decline in humans. Aging Cell. 2012 Aug;11(4):644-650. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00825.x. Epub 2012 May 21. PMID: 22510429

20. Kenyon C1, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. Nature. 1993 Dec 2;366(6454):461-4. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. PMID: 8247153

21. Bradley J. Willcox*, Timothy A. Donlon*, Qimei He*, Randi Chen*, John S. Grove*, Katsuhiko Yano*, Kamal H. Masaki*, D. Craig Willcox, Beatriz Rodriguez*,and J. David Curb*,

FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. http://www.pnas.org/content/105/37/13987.long

22. Cynthia J. Kenyon. Insulin/IGF-1 and FOXO signalling affects mouse and human lifespan.

Nature 464, 504–512 (25 March 2010) doi:10.1038/nature08980

23. Mercken EM1, Crosby SD, Lamming DW, JeBailey L, Krzysik-Walker S, Villareal DT, Capri M, Franceschi C, Zhang Y, Becker K, Sabatini DM, de Cabo R, Fontana. Calorie restriction in humans inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway and induces a younger transcription profile. Aging Cell. 2013 Aug;12(4):645-51. doi: 10.1111/acel.12088. Epub 2013 Jun 5.

24. Luigi Fontana, Samuel Klein, John O. Holloszy, and Bhartur N. Premachandra

Effect of Long-Term Calorie Restriction with Adequate Protein and Micronutrients on Thyroid Hormones

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.2006-0328

25. Roth GS1, Handy AM, Mattison JA, Tilmont EM, Ingram DK, Lane MA.

Effects of dietary caloric restriction and aging on thyroid hormones of rhesus monkeys. Horm Metab Res. 2002 Jul;34(7):378-82 PMID: 12189585

26 . Leanne M. Redman, Johannes D. Veldhuis, The effect of caloric restriction interventions on growth hormone secretion in non-obese men and women

27. 1 Tam CS1, Frost EA2, Xie W2, Rood J2, Ravussin E2, Redman LM3; Pennington CALERIE No effect of caloric restriction on salivary cortisol levels in overweight men and women. am. Metabolism. 2014 Feb;63(2):194-8. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.10.007. Epub 2013 Oct 24. PMID 24268369

28. Luigi Fontana , Dennis T. Villareal , Edward P. Weiss , Susan B. Racette , Karen Steger-May , Samuel Klein , John O. Holloszy. Calorie restriction or exercise: effects on coronary heart disease risk factors. A randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and MetabolismPublished 1 July 2007Vol. 293no. E197-E202DOI: 10.1152/ajpendo.00102.2007.

29. Weindruch R, Walford RL, Fligiel S, Guthrie D. 29. J Nutr. 1986 Apr;116(4):641-54.

The retardation of aging in mice by dietary restriction: longevity, cancer, immunity and lifetime energy intake PMID: 3958810

30. Fontana L, Klein S, Holloszy JO, Premachandra BN. Effect of long-term calorie restriction with adequate protein and micronutrients on thyroid hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Aug;91(8):3232-5. Epub 2006 May 23. PMID: 16720655

31. Soare A1, Cangemi R, Omodei D, Holloszy JO, Fontana L. Aging (Albany NY). 2011 Apr;3(4):374-9. Long-term calorie restriction, but not endurance exercise, lowers core body temperature in humans. PMID: 21483032

Article reviewed and updated: July 2019.

awesome